“It was a matter of life and death”

What was it like giving birth preterm 40 years ago? And how does it affect an adult today, who was born preterm back then? Juliëtte Kamphuis from the Netherlands was born preterm in the 1980s. In this interview, she and her parents Joke and Theo Kamphuis, told GLANCE about their very personal experience back then. Also to share this with other parents today.

Question: Mr and Mrs Kamphuis, your daughter Juliëtte was born preterm in the 1980ies. How was the situation in the neonatal unit back then?

Joke Kamphuis: Our daughter was born in a regional hospital located in the Eastern part of the Netherlands and it was immediately clear that this hospital did not have special expertise and the facilities to keep her alive. It was a matter of life or death.

Theo Kamphuis: While Joke was recovering from the delivery, the paediatrician-neonatologist spoke to me separately and briefed me on the situation and how to proceed further. It was a clarifying conversation about the situation and the paediatrician did not conceal how serious it really was. The medical team gave me advice on how to care for my child, even though they already took their responsibility and decided to transfer our very preterm daughter to the neonatal intensive care unit of an academic hospital.

Meanwhile, the paediatrician-neonatologist called several NICU’s in the Netherlands and it was difficult to find a place for our baby – because they were all full. It was very clear to us that if they could not find a place in a NICU, our daughter was going to pass away soon. Luckily, they found a place in a NICU in the Mid part of the Netherlands. Together with the medical team, we decided immediately to transfer her to the NICU of this academic centre which was 130 km away. I accompanied my baby girl in the ambulance since there was the risk she would probably not survive the transport.

During the transport to the NICU; the professionals informed me about the arrival at the academic centre and about the further approach and treatment of my child. The transport lasted 1.5 hour and the medical team went through various scenarios with me: “If this or if that” will happen in the coming days followed by “For you as the father it is very important to know”. They gave me lots of information, which was very valuable to me afterwards.

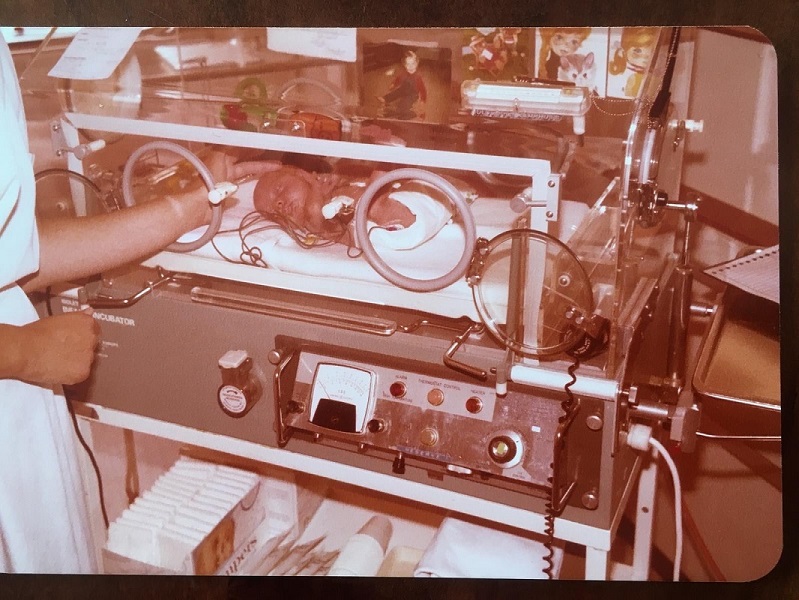

Joke Kamphuis: During the transport, the physician and assistants were constantly busy with our daughter in the incubator and reported their observations to the NICU of our regional hospital by radio communication.

Theo Kamphuis: Thus, upon arrival, the whole medical staff was prepared and ready. After a full examination of our baby, the medical team attached her to a mechanical ventilator and stabilised her.

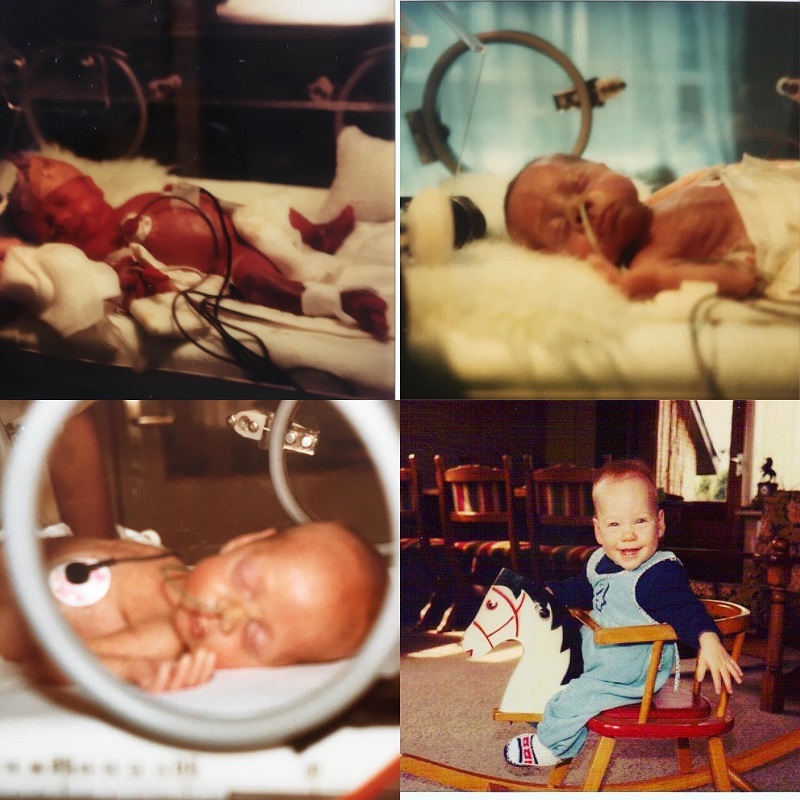

After arrival some hours passed until I saw my daughter again in the incubator. In the meantime, the discussions with the medical team continued and some photos of our baby girl were taken, to show them later to Joke. The medical team asked me questions like “What should we do if she does not make it?”, “Are you religious?”, “Should she be baptised?” or “What should be her name?”. And from the moment I announced the name of our daughter to the medical team, they did not call her anymore “baby” or “girl”, but “Juliëtte”. Suddenly our daughter had become a real human being, and this gave us hope. As a father I experienced the conversations with the medical team at the NICU of the academic centre as extremely valuable. When I returned to the regional hospital, I was able to share my feelings together with my wife, and with the first 2 photos of Juliëtte in our midst.

Joke Kamphuis: This gave us both hope and strength. If we hadn’t had these warm conversations with the medical staff from the start, then we might have felt less bonded with the medical team and, of course, also with our daughter. Most of our questions were answered by the medical team before they even occurred to us.

Theo Kamphuis: Also, the advice of the paediatrician-neonatologist of the regional hospital was very valuable when Juliëtte was born, because his advice gave us courage and hope. He urged me as a father, to not let our newborn baby alone during the ambulance transport, but to accompany her.

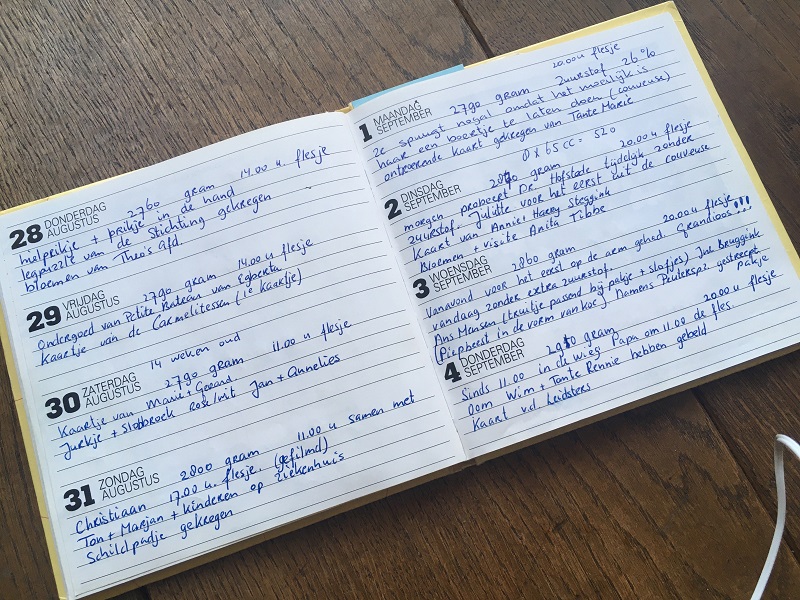

Even in the NICU in the academic centre, we were always encouraged to keep in touch by phone or to visit the NICU. The photo of our oldest son and some nice birth cards of family members were attached on the incubator and the medical team assured us: “She feels it”. Although it took awfully long 3,5 months until we could hold Juliëtte for the first time, we were encouraged to touch her little fingers or her head. It was very important for us as parents to be able to touch her and to connect with her, and also for our baby girl since she could feel that.

Joke Kamphuis: After 3 months Juliëtte was transported from the academic centre to a regional hospital near our home address, where she stayed for another month. We experienced a big difference in the “warm welcome” as parents between these centres. Our observation was after returning to the regional hospital, suddenly nothing was allowed anymore. No physical contact with Juliëtte for instance and we experienced a strong difference in the kind of care. In the academic centre, physical contact was a priority – only touching our baby, as holding her was not possible at that time. At the regional hospital, they thought that this was not “medically sterile”. For example, photos were not allowed anymore on the incubator. We felt that the fear of contamination should never be at the expense of physical contact between parents and their baby, as a baby feels connection by touch. We as parents felt very strongly the difference in guidance of nurses at the academic medical centre versus at the regional hospital. This should be done differently especially if this still is the case in some centres.

We also felt that follow-up after discharge of NICU should be more frequent and longer for a preterm child. In our situation, it was only once a year a brief interview of 30 minutes and answering some questions for us as parents. We would have had expected that there would be much more done and also more thorough research on Juliëtte’s health. The visits were only face-to-face. And after 5 years of follow-up the medical team stopped visits very suddenly, without discussing this with us as parents or asking for our agreement. “She is now equal to every other child”, they said.

We really felt left alone. “What if something happens again?” we thought. We were constantly informed by the medical staff about the short-term and long-term consequences of preterm birth and the possible adverse reaction of the medical procedures, which used to keep Juliëtte alive. Some of those medicines were quite new at that time, and possible long-term or late effects on the health of preterm babies weren’t known yet. Therefore, we asked if these medicines could have adverse reactions in later life. The answer of the medical physician was: “This could happen to every other child”. But according to us, other parents have not lived in such a fear for the first 5 years of their child’s life. And now we know, that our daughter has a chronic lung disease which started at the age of 25. So we think: The follow-up of a preterm baby should be much longer, if even, life-long.

Mr and Mrs Kamphuis, your daughter was born nearly forty years ago. Back then, it was common practice to separate preterm babies from their parents. Which impact did this separation have on you as parents and do you think it might still affect the relationship to your daughter today?

Joke and Theo Kamphuis: Well, this is very difficult to answer. After all, the separation was a medical necessity, which does not mean that we had no access to Juliëtte at all. We had very intensive contact with the academic hospital and were allowed to call as often as we needed to. The medical team always had time to speak to us.

Joke Kamphuis: After nine days of recovering from the delivery, I drove to the NICU of the academic medical centre. This was the first time I actually saw my daughter. I always believed that Juliëtte would make it, but I also knew how critical the situation was at that time, and how low the survival rate was. Theo and I are both very down-to-earth and at the beginning we put our emotions aside, as there was no place for them. But this does not mean that there were no emotions at all. We discussed a lot with each other about the situation in the NICU and also afterwards. But we always reconciled and found a common path in life. When I, as a mother, answer this question, my emotions emerge strongly. Perhaps this has something to do with my age, I am 71 now.

The relationship with Juliëtte has always been very positive and we let her grew up as a “normal” child and not as a “disabled” child. We did that unconsciously. But now we think that it only made Juliëtte stronger – both physically and mentally.

What do you think could have been different, if both of you would have had more contact with your newborn daughter?

Joke and Theo Kamphuis: It would have been better for us as parents, if we had more physical contact with Juliëtte. You can handle your overwhelming emotions better when you touch your child. But we are both forward-thinking and believe that looking into the past is not very useful, because you can`t change anything.

Juliëtte Kamphuis, you were still a baby when you were separated from your parents. Do you think this early separation had any consequences on your life as a child, a teenager or an adult?

Juliëtte Kamphuis: My parents tried to visit me in the NICU as much as possible, although it was not always easy due to the distance, and they also had to take care of my 10 months older brother. It took a long time before my mom was finally able to hold me. I was born on the 24th of May, and my mom held me for the first time on the 3rd of September.

Perhaps it would have helped me as a baby in the NICU, if my parents had had more contact with me, for example holding me earlier. It may have helped to comfort me in certain situations, such as supporting me in pain management during some medical procedures which I know now must have been painful. It may have helped me feel less uncomfortable as a toddler later in life because I perceived an environment with loud noises often as very stressful. I think that this has something to do with the loud noises I experienced when I was in the incubator. An incubator works similar to a sound box of a violin or guitar, and it produces strong resonances inside if there is some noise on the outside that on itself is not even that loud.

Even though, I think I must have felt somehow the presence of both of my parents and especially the strong belief of my mom that I would make it, since I never gave up. I know that my parents really wanted me as their child and I was loved from the beginning.

Mr and Mrs Kamphuis, how do you feel, knowing that parents worldwide are very often not even allowed to see their newborns in the neonatal units because of the COVID-19 pandemic?

Joke and Theo Kamphuis: We feel this is awful, it shouldn’t be the case. For parents it gives hope to see their newborn baby, and it will support parents throughout emotional difficult times. What if the baby dies without the parents having seen him or her? This is very traumatic for the parents and emotionally extremely difficult and almost impossible to cope with.

Theo Kamphuis: And this is exactly why the paediatrician-neonatologist advised me to accompany my daughter to the outpatient clinic in 1980. Because he knew how traumatising it would have been for me as a father, if Juliëtte had died during the transport. That’s why we want to emphasize that there should be no separation at all.

“Every parent worldwide should be allowed to visit their newborn infant in the NICU, even during COVID-19. This is best for the parents and their child and prevents possible adverse outcomes due to a separation.”

Joke and Theo Kamphuis

Ms Kamphuis, as a former preterm baby, what do you think needs to change in the current situation?

Juliëtte Kamphuis: I do agree with my parents that there should be no separation. Parents should be allowed to visit their newborn baby. It will help both, parents and the baby, to feel connected by being present and by touching each other. I know for sure that a baby feels this connection and it will support the baby through each critical health-related situation. Medical centres and NICUs, should take these matters into consideration and think about what is best for the baby and the parents. If babies can’t connect with their parents, they could experience more difficulties in bonding with their parents when growing up and may experience more difficulties in interacting with peers or in building relationships in later life. And, as mentioned by my parents, it is very awful to think of that somewhere worldwide during COVID-19 babies pass away, without the parents having a chance to see them.

It is possible for parents to take COVID-19 regulations into account while still being able to see their baby, by taking precautions. The hospital can adapt the route to walk to the NICU in order to prevent visitors to cross pass or pass each other on the same route, parents could wear masks, they could try not to visit friends or other family members unnecessarily.

We thank Joke, Theo and Juliëtte Kamphuis for these personal insights in this interview and for their support for the “Zero Separation. Together for better care” campaign!